Summer Ends

Can it really be? Joyous day! The months of waiting are finally behind us. Sabrina Carpenter’s Short and Sweet is out on all streaming platforms. Not a moment too soon, it is the natural bookend of Girly Pop Summer.

Brat Summer has been a defining element of 2024. We have enough think pieces and video essays about BRAT to last a lifetime. An uncontested touchpoint in the current zeitgeist, it hasn’t been without company; this summer has been punctuated by a resurgence in regard for pop music.

By nature of my being a white woman who came of age in the early 2000s, I will always carry some sort of affinity for Taylor Swift. But on the whole, I can’t say that I would typically consider myself a pop music fan (I’m known to gravitate more towards a Fiona Apple “Please Please Please” than a Sabrina Carpenter). This summer has been different.

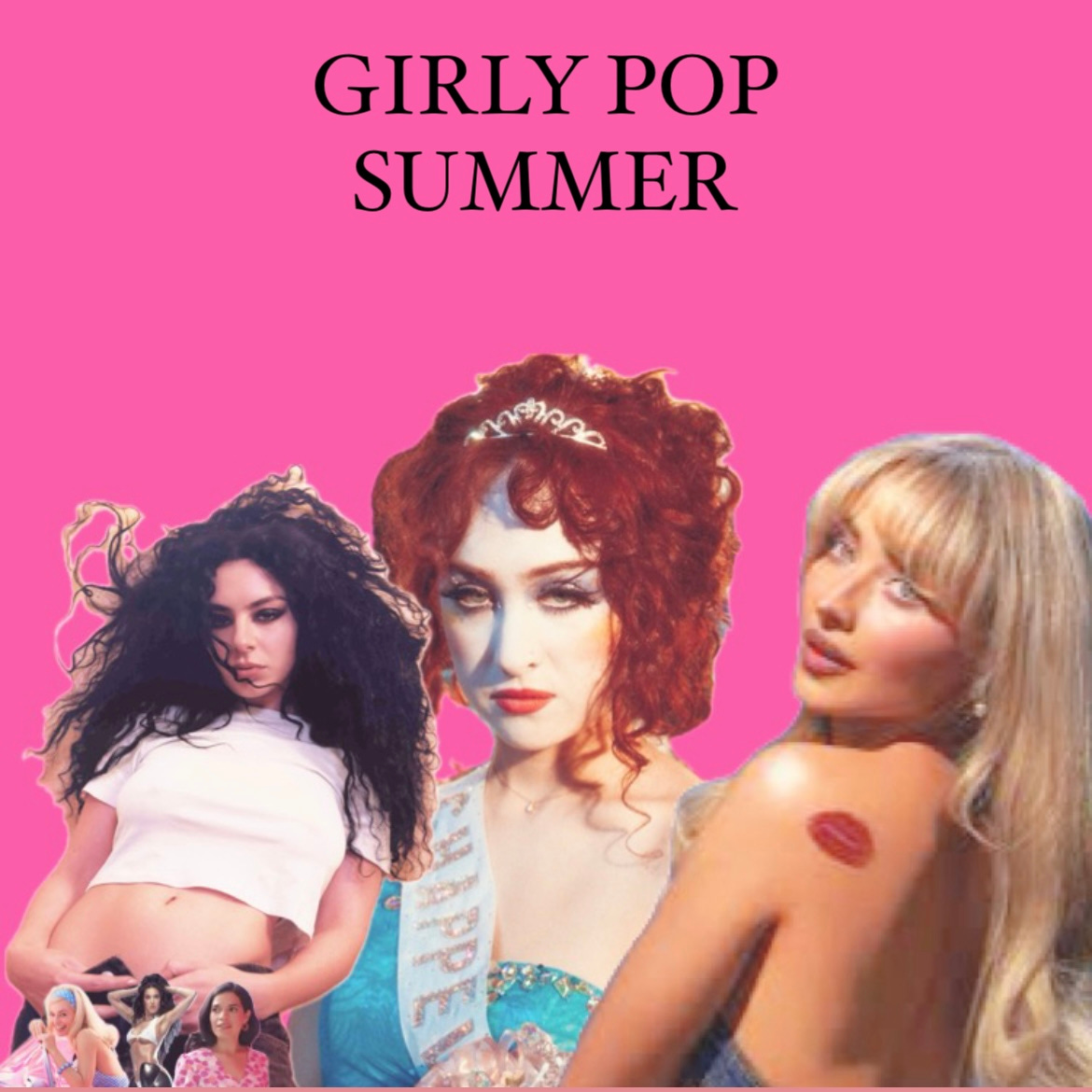

There’s something that’s been incredibly healing about dancing to the bubblegum pink-coded beats. Part of it is that essence of bubblegum-pink. It’s a reinvigoration of the genre that’s been led by a trio of would-be Powerpuff Girls flying in V-formation: Chappell Roan, Charli xcx, and Sabrina Carpenter. I’d like to take this moment to thank our girls for their service.

Pop Music’s Moment

Earlier this summer, the New York Times declared that Chappell Roan and Sabrina Carpenter saw a gap in the pop music market, and filled it. Previously dominated by multiple Swift mega deluxe platinum digital albums with bonus acoustic tracks, pop now had new, exciting, and refreshingly original musical acts. Rectifying the staleness within the genre is what has prompted pop music to take back the reins as an agent in cultural relevance beyond its fan base.

Notwithstanding that pop music is named so because it is “popular,” in that it receives radio play due to its being palatable, accessible, and generally unchallenging for consumption by a wide range of audiences, it has not been culturally significant in the way that other genres tend to be at certain moments in time (like rap and hip hop in the 2010s, or rock in the 1970s). The Critics at Large podcast from the New Yorker notes that while pop music has crept back into the driver’s seat as a force in culture-shaping, it isn’t all encompassing. It’s Charli, Chappell, and Sabrina in specific.

Katy Perry’s “Woman’s World” released this summer to almost immediate failure. Her latest attempt at re-entry to the confederation of sitting pop royalty was ridiculed online for what can only be described as cringe factor.

“Woman’s World” is an archetypical neoliberal white feminist anthem. It’s perfect for an H&M store’s speakers, but it wouldn’t make it onto a pregame playlist. Perry attempted to salvage the song by claiming it was satirical, but the damage had been done. It read as dead serious. She, and the song, were branded with the strain of #Girlboss Feminism that ruled the mid 2010s, but is largely rejected by young feminists today.

A more intersectional feminism that is critical of capitalism (at its core, antithetical to #Girlboss Feminism and the perpetual expansion of the capitalist machine) prefers its women-centric art to be more nuanced. Statements like, “Women are AWESOME!” are regarded as vapid, uncritical, and unhelpful. We know women are awesome; how does this help save us from institutional violence? Alleviate your male coworker’s incessant mansplaining?

It makes sense why “Roar,” a song similar in sentiment, did well upon release in 2013, and why “Woman’s World” flopped ten years later. It’s hollow in the same way that the Barbie movie turned out to be.

Barbie’s A for Effort

Last summer, Barbie was the dominant cultural obsession. Movie-goers showed up to theaters in droves, clad in pink and clothed in one central belief: this movie would heal something in them.

Barbie dolls are symbols of femininity in the most basic, normative sense. They represent women, grown women (with boobs) replete with outfits, ensembles, and accessories. They are sold to very young girls.

The Barbie movie positioned the Barbie doll as a tool (toy) for girl’s empowerment: Barbie is all that young girls can see themselves in, and all that they could be (an astronaut, a mermaid, the president). The movie addressed the criticism that Barbie is, at the same time, incredibly disempowering.

As seen in the character Weird Barbie in the movie, girls of a certain age will begin to mutilate their dolls. They chop hair off, remove a leg or a head; the movie said it was the result of a Barbie that had been “played with too hard.” Researchers suggest it is a reaction to Barbie as a hate figure.

Young girls begin to see Barbie as the culmination of what they are up against: their elementary understanding of what beauty standards are, why they are inherently oppressive, and how women are disproportionately burdened by them in society are unleashed on the dolls. The movie’s breaking of the fourth wall to acknowledge the irony in Margot Robbie discussing normative standards of beauty while being the beauty standard still does not absolve the internalization of these concepts. In fact, it’s lazy.

The makers of the movie chose to frame the climax in America Ferrera’s monologue. Their failure was the positioning of this speech as a groundbreaking realization: women “have to be thin, but not too thin.” Yeah, we know-- and we’ve been beating up our Barbies ever since we realized. Like Perry’s “Woman’s World,” Barbie had an appearance of being empowering, while actually being incredibly basic.

This isn’t to say that the movie didn’t have a certain impact on the celebration of womanhood. Its role in healing the wounds of being socialized as a woman might have been most effective in, of all things, the embracement of the color pink.

Pink Hating

Around the same time that girls take out their dissatisfaction with beauty standards on their Barbie dolls, they also go through a period of Pink Hating. They enter a phase in which they reject symbols of traditional femininity.

When toddlers begin to understand gender as it has meaning in our society and culture, they conceive of it through the lens of gender signifiers. They view normative performance as gender; girls wear makeup and so wearing makeup makes someone a girl.

Upon understanding gender as a social group which they belong to, girl toddlers seek to embrace the signifiers of that gender to reaffirm their membership in the girl gender group. They enter a phase of Pink Loving.

A 2011 research paper found that girls aged 3 to 4 develop obsessions with pink frilly dresses; they refuse to wear anything else. These girl toddlers understand pink frilly dresses as items which belong to the girl gender group. Wearing them is how they communicate to the world that they also belong.

Though Pink Loving is overwhelmingly prevalent in toddlers, girls in the middle-childhood age group (5 to 8 year olds) maintain an almost vitriolic hate of pink and other female-typed activities and interests. Research says that as girls mature, and they develop a better understanding of the social status of gender groups, they begin to reject normative signifiers of femininity, and embrace symbols of masculinity. In their sudden re-orientation towards male-typed identifiers, they hope to transition to a higher status social group.*

You can see this repeated in the “not like other girls” phenomenon, in which young women will position themselves away from other women, emulating traditionally masculine traits and dismissing or diminishing those traditionally female traits.

Being a “not like other girls” girl has been rightfully memed by this point, and a trend on TikTok went viral of former Pink Haters who are now pink collectors. In the trend, young women who fell victim to Pink Hating as a rejection of their girlhood now seek to reclaim it.

What Is Girlhood Anyways?

Girlhood is practically the only thing that anybody can seem to write about these days (myself very much included). It’s been inspected, dissected, and ruminated on so many times over that it has nearly lost all meaning, but essentially, girlhood is a catchall term for anything that more than one woman experiences, especially as it relates to relationships between women.

When I was in college, I never knew where my Revlon hair dryer was; it was either in my roommate’s room, or my other roommate’s room, or my best friend’s room who lived down the hall. Even though it was mine, it belonged to everyone. That is girlhood.

My boss still has my favorite scrunchie. During my first week of work, about a year ago, I leant it to her. I’m still too scared to ask for it back. I believe this is girlhood too.

Jia Tolentino recently wrote an essay for The New Yorker about the Sephora Tween phenomenon - in itself, another form of girlhood. She says,

“Like seemingly half the women in Brooklyn, I happened to be reading Miranda July’s novel “All Fours” at the time, and had dog-eared this quote: ‘So much of what I had thought of as femininity was really just youth.’ These days, children want to look like tweens, tweens want to look like teen-agers, teen-agers want to look like grown women, and grown women—dreaming of porelessness, wearing white socks and penny loafers and hair bows—evidently want to look like ten-year-old girls.”

Young girls act like grown women, and grown women mimic young girls. The lines of girl/womanhood are blurred so that they are practically one in the same-- and even if girls are not yet women, women are most certainly girls.

The “girl” rhetoric, like the idea of girlhood, has taken over all forms of memetic communication on the Internet. “Clean Girl,” “Rat Girl,” “girl dinner,” “hot girl walk,” and, famously, being “just a girl” are digital constructions of femininity that are absorbed by women in the real world. A fair amount of criticism has been applied to the “girl” meme. It is argued that calling oneself a girl is infantilizing to one’s womanhood.

Being “just a girl” references the No Doubt song where Gwen Stefani sings about the frustration of being limited by girlhood. She is “in captivity” because of her gender, and is frustrated with a system that devalues her personhood in favor of her girlhood: that is all they’ll let her be.

Today’s concept of “just a girl” has been preverted to the inverse of what Stefani sang about. A woman can blame anything on being “just a girl.” Being “just a girl” means being “just a [little] girl,” which means “just a child” which means “just someone who is incapable of functioning as a fully grown human person with autonomy and intelligence.”

“Girl dinner” is a diminutive, affectionate name for what could be a handful of grapes and a slice of cheese. This may be enough to feed a little girl as a snack, but certainly would not constitute a meal for a grown woman (“boy dinner,” usually a slab of meat, is at least protein-packed and life sustaining if lacking variety).

Women don’t consciously, intentionally participate in the devaluation of themselves by playing into silly Internet trends. But they also don’t consciously, intentionally subscribe to the idea that women are inferior to men by becoming Pink Haters. Actually, becoming a Pink Hater is an effort to do the opposite.

And when femininity is embraced by the time middle-childhood girls reach tweenhood (ages 9 to 12), they do so through the emulation of grown womanhood. That is, through cosmetic purchases, skincare routines, and retinol treatments.

If gender is linked to performance, and normative femininity is linked to beauty standards, girl/womanhood then becomes linked to the material consumption of goods that signify femininity. The expression of gender can’t merely be an expression of oneself, but an expression of one’s consumption. This, in essence, is what middle-childhood girls reject: the superficiality associated with the performance of femininity.

Womanhood as Consumption, Consumerism, and Complicity in One’s Own Oppression

Different from sex, gender is socially constructed: it is considered in the context of place, time, and culture.

Pink isn’t inherently feminine. It’s been an exclusively “feminine” color for less than a hundred years. Pink being used for little girls only became popular in the 1980’s with the prevalence of prenatal testing and the expansion of gendered baby clothing.

Pop music isn’t gendered either, even if a majority of its listeners are women. Still, pop music is considered “girly.” Things that are “girly” are often considered vapid. The vapidity, or the superficiality, in girliness is linked in the pursuit of beauty.

Women and girls are taught that to be women, to reaffirm their identity as women, they must emulate cultural ideas of normative femininity. Emulating normative femininity, in popular society, means conforming to normative beauty standards. Yet conforming to normative beauty standards is seen as shallow and trivial.

America Ferrera’s character did have a point. She goes on, “you can never say you want to be thin.”

Kelefa Sanneh, a guest on the Critics at Large podcast says that the “celebration of superficiality” in “Please Please Please” is the essential nature of how pop music excels.

It is this, ultimately, that delivers the healing properties inherent in me espresso (and red wine supernova, and apples).

Through their music, Charli, Chappell, and Sabrina communicate an embracement of girlhood that leans into normative ideas, but in a tongue-in-cheek, post-ironic way.

Where “Woman’s World” and Barbie read as superficial in practice, the music of Chappell, Charli, and Sabrina are superficial in virtue and belief; and they give you a wink while they sing about it.

This self-referential awareness is understood and embraced by audiences in a way that makes the music fun. Girls and women can embrace superficiality with an awareness that it will be part of their perceived gender-hood, whether they are toddlers or tweens. They can be in on the joke rather than trying to prove themselves exempt.

At the same time the traditional femininity is embraced, each Pop Girly brings a sort of subversion that creates a new multi-layered understanding of what it means to be feminine: Charli xcx is a brat. She goes to raves and does hard drugs. Chappell Roan is queer, and sings about lesbian relationships. Sabrina Carpenter takes pride in her promiscuity. Her song “Juno” on the new album literally says, “I’m so fucking horny.” These aren’t attributes typically associated with the girly popstar persona, and so they break down the mold of normative femininity while still maintaining an ethos of girliness.

Make no mistake, these women do conform to traditional ideas of femininity in that they are thin, conventionally attractive white women. But they don’t try to convince you of anything otherwise. They embrace their girliness full-on, and make a sort of spectacle out of it.

Thank You, Pop Girlies

Chappell, Charli, and Sabrina are silly. They are campy and unserious--and they don’t pretend like they aren’t; they don’t act like they’re some great feminist thinkers who break down barriers so that women can touch the glass ceiling.

They sink into feminine aesthetics. They take pride in what they are at once conforming to and subverting. In doing so, they heal the childhood wounds of a girl who might have suppressed her femininity. They appeal to the grown women who might remember doing so. They offer a path to reconnect with what once might have been shameful.

A girl/woman is capable of being strong, and of being hyperfeminine, and she doesn’t need you to spell this out for her. Femininity is strong. We know that.

Think about the last time Katy Perry was truly the it girl of pop -- it was during her Teenage Dream era. The lead single: “California Gurls.”

*Note this is not the same thing as instances of gender dysphoria in transgender people.