All things considered,

I’ve been the “crazy” girl before. I could go through the list: I poured a fully full White Claw on an ex-boyfriend’s head when I walked in on him with another girl (no, we weren’t technically dating at the time even if we were actively hooking up and going on dates. Yes, I still miss my White Claw). I wrote and gifted a short story to a situationship who was leaving the country which, in hindsight, might’ve been an inadvertent love-bombing manipulation tactic (but two weeks later he went to visit another ex-situationship in Budapest, and I’d only found out after he’d come and gone a second time, so really, who’s keeping score?). I’ve written shitty poetry about one-night stands. I’ve started imagining life with a guy 72 hours into the talking stage. I’ve prayed to God and asked Him to send me the cute guy I walked past on the street. Could this conversation be saved for a therapist? Too late.

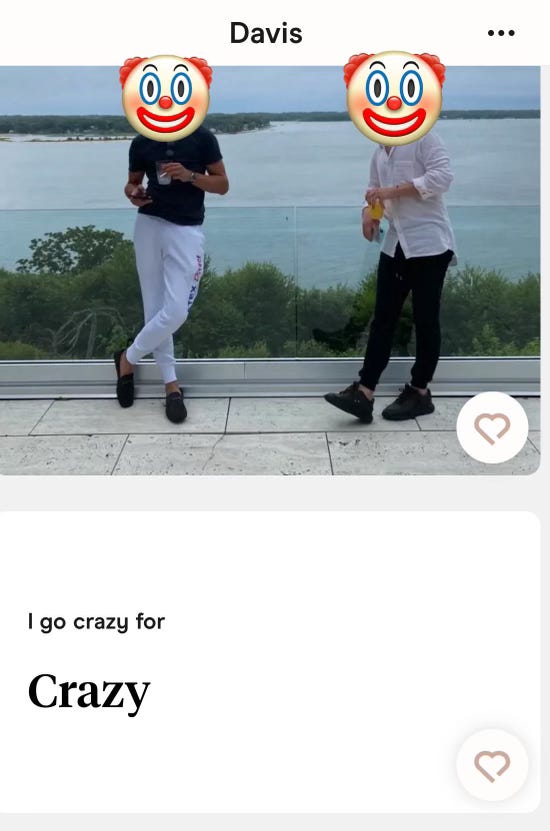

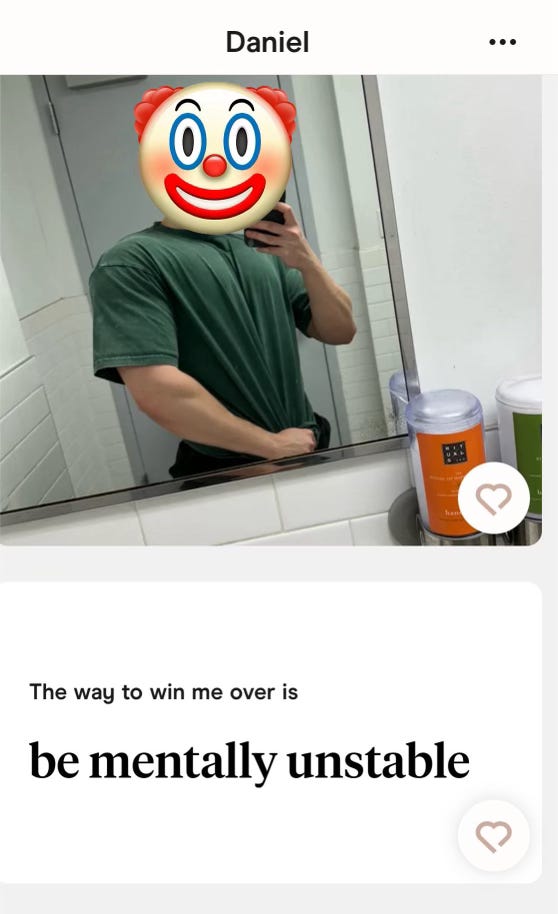

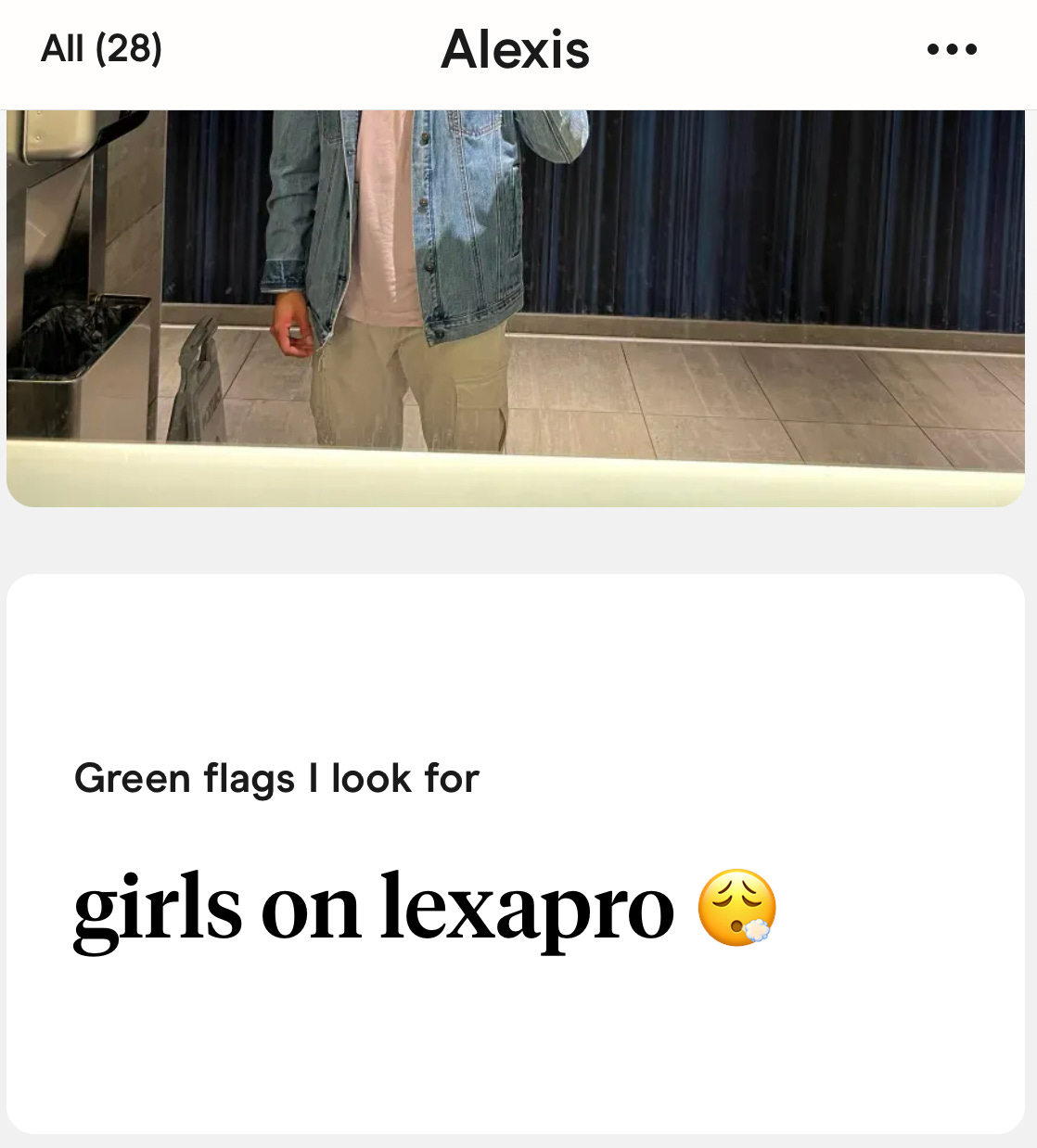

As fate would have my scrolling through Hinge when trying to decompress after a long day, I’ve noticed there is a trend. Potential suitors claim to be looking for someone who is “crazy,” “mentally unstable,” or, most popularly, “on Lexapro.” Last summer, I was further made aware of this affection that men seem to take with mentally ill women. On a night spent drinking with a close friend and another distantly peripheral male friend, he told us (unprompted) that his type in women were, and I quote, those who take “grippy sock vacations” i.e. women who are admitted to mental hospitals. We don’t hang out with that guy anymore.

I’ve never taken a grippy sock vacation (and for the record, I don’t think I’ve ever even used that term before now). But I have called myself “crazy,” mostly in an effort to be transparent with whatever guy I was dating at the time. What I meant is that I can be jealous and impulsive. Almost every one of those guys assured me that they loved crazy girls. The thing is, they didn’t.

Ex-boyfriend with sticky raspberry flavored White Claw hair grew tired of my accusations that he was cheating (spoiler alert: he was, and this time, we were actually dating). Ex-situationship I’ve immortalized in Google Docs became withdrawn and shut down when I asked why his iPhone keyboard carried a Bitmoji in the likeness of his ex-situationship.

There seems to be some kind of disconnect I’m not fully understanding.

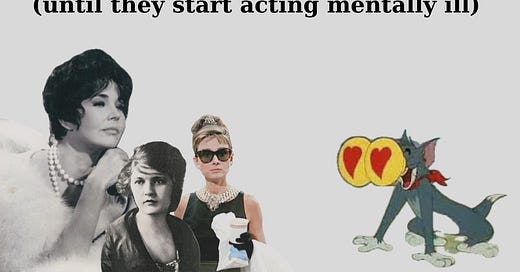

The idea of romanticizing “craziness” (or, mental illness) is not new. So much of art centers on the turmoil of the mind. One might argue that the most emotionally evocative art is that which deals with the inner struggle. Many artists were famously mentally ill (Van Gough, Cobain), and many have made famous art about mental illness (Edvard Munch’s “The Scream,” Ariana Grande’s “Fake Smile”). The idea of a woman being mentally ill, and being hot and mentally ill, and perhaps being hot because she is mentally, however, is an attitude that frequently appears in art produced by men.

In 1958, Truman Capote published Breakfast at Tiffany’s in the November issue of Esquire Magazine (and in 1961, the film adaptation starring Audrey Hepburn was released to immediate critical and commercial success). Though the film differs in many ways to the novella, the titular character, Holly Golightly, remains the central subject; and, while the film is certainly happier in a sense, the conflict in her character holds both on screen and in text. Holly Golightly is, first and foremost, hot (and of course, Audrey Hepburn is a timeless beauty). Additionally, Holly is stylish and chic. She’s popular. She’s called a “glamour girl.” She’s an enigma. She is also a deeply, deeply sad person.

Capote conveys in Holly a hot sad girl, but also an exciting hot sad girl. She is quirky. She frequently makes frenetic, almost manic monologues. She plays her guitar and sings sad songs on her fire escape about wanting to escape.

Holly struggles with the very human emotions of loneliness, isolation, and what she calls the “mean reds,” yet she is almost unhuman in her superficial character -- her magnetism, charisma, and physical attractiveness that makes her so captivating. Holly is full of these kinds of paradoxes: she is girlish and sweet, but incredibly calculating. She receives a steady flood of calls and party guests, but talks about her belonging to no one, and being alone in this world. She is canonically a lesbian, but looks for a rich man to marry and take care of her. She is admired by everyone, and yet, everyone seems to agree that there is something wrong with her. The word “crazy” appears four times throughout the novella, each time in reference to Holly.

In the opening scene, the narrator and neighborhood bartender wonder about Holly’s whereabouts. The narrator says there are two possibilities: Holly is either dead or in a “crazy house.” When Holly suffers a nervous breakdown after receiving news of the death of her brother, her fiancé bemoans her “conducting like a crazy” and soon breaks the engagement. Her lawyer describes her character and says, simply, “she’s crazy.” Towards the end of her story, Holly puts the label on herself saying, in reference to the breakdown, “now do you see why I went crazy and broke everything?”

It’s well understood that Holly is universally loved. But to be beautiful and elegant isn’t enough to be loved and admired. One must hold a certain quality of fascination to attract others to such a degree, and to make them so attached. Her mania is endearing because she is hot. Yet when this energy reaches an emotional peak, she is deserted. She is left to deal on her own. During her nervous breakdown, her fiancé asks if “her sickness is only grief.” Indeed, for her grief she is sickened.

In a similar way to Holly Golightly, the characters in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender is the Night presents a sort of paradox in their outward repose as fabulous and wealthy people vacationing on the French Riviera, and the true deficiencies of their character (modern day readers might be reminded of popular television show White Lotus). The novel essentially follows the demise of main character Dick Diver, a famed and well respected psychologist. We soon learn that his wife, Nicole, is his former patient. Throughout the novel Nicole has numerous breakdowns as a result of her mental instability and trauma. While his marriage falls apart, Dick also pursues a relationship with a young actress by the name of Rosemary.

The novel supports the idea that the reason a mentally ill woman might be attractive is because she is vulnerable, and easy to manipulate. In the same way that Dick enters into a relationship with a woman who is vulnerable because of her mental health, he pursues a relationship with a woman who is vulnerable because of her age and immaturity. Dick is a groomer, and ultimately falls from grace by the end of the novel, but the point of the irony in his predatory behavior is that it is covered up by his wealth, clout, charm, and good looks. It’s unclear if Scott was aware of the irony within himself.

It is well known that Scott put pieces of real-life into every character he’d ever written (his first novel, This Side of Paradise is largely autobiographical, while Tender is the Night chronicles the relationship between him and his wife). Zelda Fitzgerald, another famously mentally ill woman who was institutionalized for most of her life, was the muse for every heroine he had ever written. Nicole Diver, Daisy Buchanan, and Gloria Gilbert, are modeled after her beauty as well as her mental imbalances -- in this way Zelda lives on both in legend and in the lyrical writing of Tender is the Night, The Great Gatsby, and The Beautiful and Damned.

And yet, the main reason offered for Dick’s (and by extension, Scott’s) demise is because of the pressure to care for Nicole/Zelda and her/their mental illness. Look at the letters Scott and Zelda wrote to each other, and the transcript of a conversation they had during a 1933 visit to the psychiatric hospital. They resented each other for their marriage, and yet were absolutely and eternally in love with each other.

Zelda/Nicole/Daisy/Gloria are worshiped in their own right despite their mental illness, and maybe even because of it. Where there is an absence of mental illness in a female character, there is an absence of that same allure, or at least assumed complexity. Women like Rosemary, though beautiful and vivacious themselves, are shallow. A woman in Fitzgerald’s world is not capable of being beautiful, mentally stable, and interesting.

Though these female characters are beautiful and crazy, they are also incredibly fascinating. Much of this fascination, character depth, and interest comes out of the idiosyncrasies associated with or because of their mental illness. Yet, when women show signs of this mental illness, they are written off, rejected, and labeled “crazy.” It is worth noting that the history of crazy women, particularly the history of female hysteria, was used as a tool to oppress and invalidate women. This paradox -- the simultaneous fetishization and dismissal of mentally ill women -- is what makes me so uneasy about the Hinge clowns. It's the same critique that is often used to describe the Manic Pixie Dream Girl trope in film.

In sum, Manic Pixie Dream Girls are female characters who are quirky (*people have also argued that these quirks are often neurodivergent or mental illness-coded traits) yet one dimensional, and are primarily written to encourage the growth of their male character counterpart. Fitzgerald’s contemporary/adversary/frenemy Ernest Hemingway wrote extensively about Manic Pixie Dream Girls and mentally ill women too. Catherine in A Farewell to Arms, is a fragile and wounded woman, and repeatedly calls herself crazy. In fact, upon one of the first introductions to Catherine, the main character thinks to himself that she is probably crazy, and also that it’s alright if she is. Brett in The Sun Also Rises carries that same Holly Golightly-style irony, in that she is the life of the party, but constantly says she is miserable. Maria in For Whom the Bell Tolls is deeply depressed from the trauma she has endured, and is the beautiful Madonna figure for which the male character sacrifices himself to. All of these women are unattainable love interests. They are ideal fantasy women, the “goal” for the men in the novels, and moreover, the foil for the male characters’ arcs. None of them get a happy ending, partly because they are characters in Hemingway novels, but they also go underdeveloped. They serve to guide the male main character on his path to self-discovery. Hemingway at once fetishizes and undermines the female characters for their mental illness, and their Manic Pixie Dream Girl qualities.

Women, of course, are also known to fetishize or romanticize their mental illness. The feminization and romanticization of sadness is worn as a badge of honor in some cases -- in Sofia Coppola films like The Virgin Suicides, the young Lisbon sisters commit suicide, and yet every second of the film is drenched in beauty and femininity. Tumblr 2014, by now a shorthand to describe the insidious social contagion perpetuated and adopted by young girls in the early teens, glamorized severe forms of mental illness and their physical manifestations like graphic pictures of self-harm and posts about suicidal ideation. While the sad girl adopts this personality for herself, voluntarily identifying as a sad girl, it must be understood that choices are not made in a vacuum. There is something to be said for the society which gives way to the romanticization of mental illness.

Melancholia might be said to glorify feeling bad because of its promise to produce great art; it is the driving force of the archetypical tortured genius. Lana Del Rey, maybe one of the single best examples of this, has adopted a persona of being sad and being sadly beautiful. She sings about female weakness and dependence in a way that makes it seem like she is enjoying it. Further, there is the idea that sadness belongs to women, and a pleasure that comes with melancholia, the gendered nature of sadness, and mental illness representation. But there is also a difference in the way the art is portrayed. Women write about their mental illness with a far different tone.

Lady Lazarus is one of Sylvia Plath’s most famous poems. Plath, herself a symbol of feminine despair, writes her soul into Lady Lazarus. The writing is impeccable and the poem itself heartbreaking, but what makes it so sad beyond the obviously grim subject matter is the toil of her mental illness being a spectacle. She watches people watch her. And it’s degrading. Plath differs in how she portrays her mental illness: it, and she, is objectified. Her critique is in direct opposition to how Capote, Fitzgerald, and Hemingway write about women with mental illness. They do in fact make a spectacle of it.

All of this is not to say that a man can’t successfully create female characters that are troubled, complex, and also not creepy. But the lines easily get blurred.

I’m also not excusing any of these Hinge clowns for actively fetishizing women who are mentally ill, and not recognizing the actual implications of entering into a romantic relationship with a mentally ill person. But I don’t think any of the guys that I’ve acted “crazy” towards in real life are misogynists, either. I wasn’t right to act the way I did in most of these scenarios, to stick my nose in places I ought not to stick it, and I take responsibility for that. There would be countless female empowerment influencers telling me that insecurity is tired and lame, and that getting a dopamine hit from stalking one’s ex’s ex shows a lack of self love more than anything else. Maybe there’s something to that. Maybe I should listen.

Besides,

Women are crazy because men are assholes.

"girls on Lexapro" is WILD 💀 I'm mentally unstable and happen to be on Lexapro, but I hate it. It's awful. Someone who is like "that's my type 🤪" is red flagging all the way to trash folder. Holy shit.

mentally ill chicks unite 🩷 bpd things 💫